Maybe you’re an experienced writer. Maybe you’re giving it your first shot after years of being an avid reader. Maybe you’ve never touched a book in your life, but you sat straight up in bed one day with a great idea for a story. No matter who you are, you’ll likely find yourself in the position of having an idea for a story all ready to go in front of you, and yet feeling like you have nothing to write down—at least, not anything that feels like a book. What’s missing? Why the paradox? More often than not, it’s your plot.

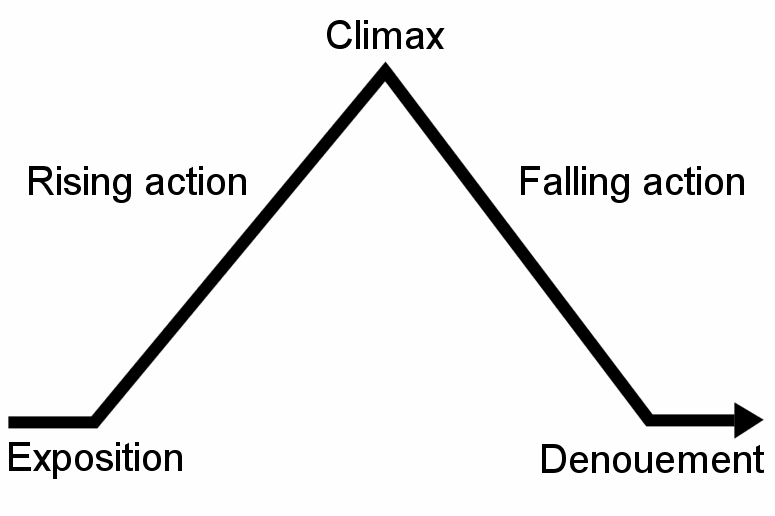

It may seem like a no-brainer. Every story needs plot, and every middle schooler has seen the plot pyramid diagram in their English class. Surely it can’t be that hard—and yet it is, even for writers who have been doing it for years! You’re not alone—plot can feel much harder to come by than concept or characters, especially for new writers.

The problem arises from the fact that a story and a plot are two separate things entirely. It’s easy to come up with an idea for a story, because a story is just the retelling of a series of events. Anyone can think of one, and anyone can call their mom and tell them the beginning to end of what happened on the bus last week. Stories happen all the time in real life because real life doesn’t care about whether or not it has plot. Plot, on the other hand, is much more specific. It’s about the selection of detail, the order in which to do the telling, what to leave out, and how to make up a story in such a way that every element lives in a carefully balanced web of cause and effect, and where the whole story is driven by some force other than just the fact that it’s being told. Luckily, there are loads of tips and tricks that will either help you turn your idea into a story from scratch, or maybe just fix that little nagging feeling that something about your plot is just off. Don’t worry—we’ve all been there! Let’s see what we can do.

Start with Conflict

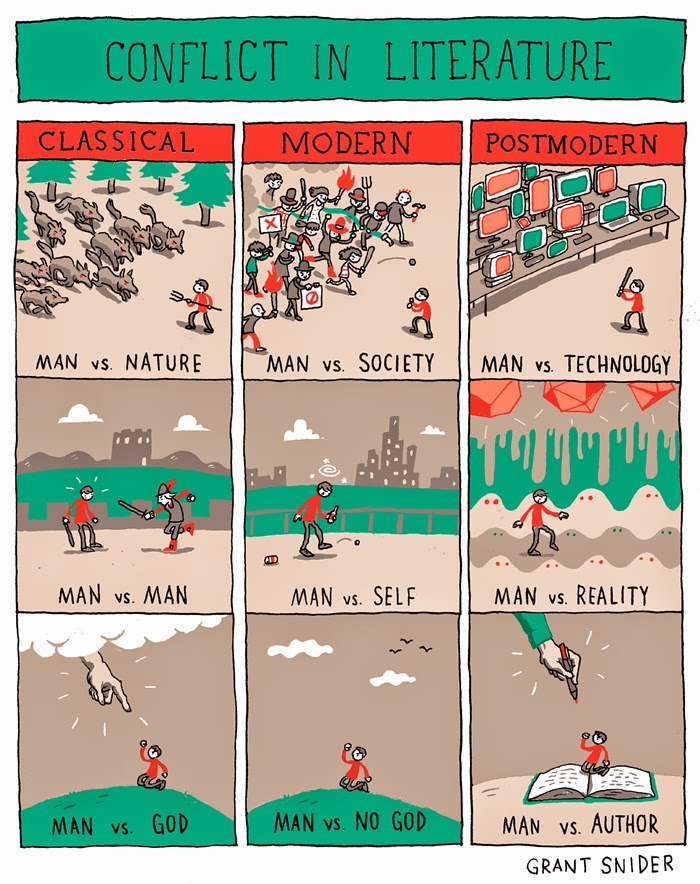

Conflict is the most essential element to plot. There are plenty of different kinds of conflict—whether your character is up against an antagonist, the environment, themselves, or some other force, the opposing wills of two separate entities are what create a story worth caring about. We all want our readers to root for our characters, and it should go without saying that this implies there needs to be something in the story acting against them. Nobody roots for a sports team standing on a field talking amongst themselves and kicking a ball around aimlessly. We root for a sports team that’s trying to win, and I use the word trying because for there to be a game at all, someone else has to be trying to keep them from winning.

A plot is the same way. Here are some good questions to think about when trying to come up with or enhance your conflict:

- What does your character want that they don’t have?

- What is preventing them from getting it? Is it another person? Why do they want to stop your character?

- Is there something your character has to do before a certain point in time? What happens if they’re too slow?

- Is there someone or something they have to save from destruction?

- Who wants to destroy it and why?

There are plenty of other prompts to get you thinking about conflict, too. The internet is your friend—no writer generates every single idea from scratch, and you should be doing research when you write; everyone needs inspiration! Sometimes you’ll find a certain type of conflict fits your form or genre well. (see Grant Snider’s expanded categories of conflict above.)

A common theme you’ll come across when asking these questions and thinking about conflict is stakes. Stakes can be as much of a driving force as your character’s desires—in many cases, they’re even more essential. Sure, your character wants something. Maybe they want it more than anything, but what do they stand to lose if they don’t get it? Even worse (which is just writer code for “better”): what might they have to sacrifice in order to get it? And is it worth it? Can they do it? While goals and desires are good for making your character strive for something, it’s important to include stakes so that they don’t have the option of just giving up on their goal when the going gets tough. This is why we say conflict drives the plot. When the going gets tough, and the easiest option is for your characters to bow out and for you to end the story right there, what forces the characters to keep going?

And remember: the best place to introduce conflict is right at the very beginning. The start of the conflict is called the inciting incident. A good inciting incident presents a problem that your character can’t just walk away from or decide to be a bystander to; it should force them to make a choice. A good piece of advice to remember when struggling with where to start your plot is to begin as close to the end, climax, and/or resolution as possible. Try working backwards!

Getting the inciting incident right can be the key to establishing a great plot, as it requires you to answer two big questions:

- What is this story about?

- Where is this all going?

You just solved the first one by laying down your conflict. Congrats! And if you want to start your story as close to the end as possible, that means deciding how the story is going to end, which is just as important so you don’t end up rambling endlessly about what your character feels like doing today, or worse, inventing frustrating minor conflicts with no end in sight. (This is the same type of slow poison responsible for the death of 15-season TV shows.)

Cause and Effect

Your inciting incident will also help you get started with another one of the essential, defining features of plot. If conflict drives your story, cause and effect hold it together. Conflict helps you decide what your scenes are going to be about, while cause and effect help you decide what those scenes will contain, how they’ll progress, and what order they’ll go in. Your inciting incident is already your first big “cause.” Then, you’ll need to decide not just what happens next, but why it should happen next according to your inciting incident. A good story is a chain reaction, and while of course it’s never taboo to include some scenes that are slower (the rise and fall of action is also important to a dynamic plot and a pleasant reading experience!) to establish worldbuilding or character development, scenes should usually be tied to the plot, triggered by the events before them, and necessary to the events after them.

A good trick to use when planning is to start every scene description or summary with a “because” statement.

For example:

-

- The inciting incident: Princess Leia Organa’s ship is intercepted by Darth Vader, who is trying to stop the rebels from using the plans to the Death Star to destroy it and defeat the Empire. (See how we know the conflict of this universe now, too?)

- Because Leia’s ship was intercepted, the Death Star plans are in jeopardy, so she hides them in a droid to and ejects them to safety along with a message to Obi-Wan Kenobi asking for his help.

- Because the droids were ejected, they end up in the hands of Luke Skywalker, who sees the message, but because of the importance of their mission, R2 escapes in search of Kenobi.

- Because R2 escapes, Luke has to go searching for him, and finds Kenobi himself.

And of course, if you’ve seen Star Wars, you know the rest from here. Luke learns about his destiny and decides to set off on his journey to rescue Leia and bring the Death Star plans to the rebels. Ta da! Cause and effect. Getting a good cause and effect chain going can give you a sense of momentum as you plan, too, making the entire process much smoother.

These suggestions are not the end-all be-all of plotting. Your story is as unique as you are as a writer and will always require some individual creativity. You know your work best!

As challenging as plotting can be, it’s also one of the most rewarding parts of crafting your story, and once you’ve nailed it, it’s worth celebrating. Try setting yourself up for success by starting with a simple outline and build as you go—you may find plotting your novel is much less daunting than you thought. You’ve got this! Good luck, and happy plotting!

written by Sophie Lanctot